“People who come out to the Caribbean from the cities and the continents go through a process of being recultured. What they encounter here, if they surrender to their seeing, has a lot to teach them.” – Derek Walcott

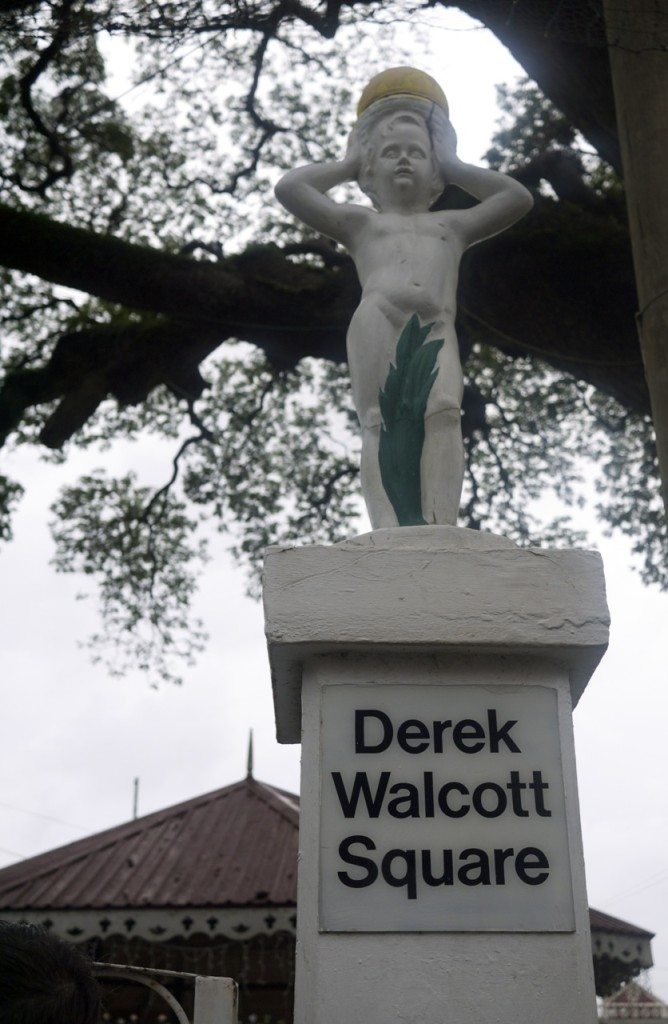

We stood in the center of Castries near Derek Walcott Square, a place that back in the 18th Century, near the time of the French Revolution, was the site of public executions. The gates on all sides were padlocked on both of our visits to St. Lucia’s capital city so we never were able to go inside. There’s a photograph of the Nobel Prize winning writer (who was born and grew up in Castries) enlarged, framed and protected behind glass.

You could see the heat rising off of the sidewalks that day and inside the square, three homeless men who must have hopped the fence sheltered from the oppressive tropical heat underneath a bandstand and the added shade of a massive samaan tree that’s supposedly some 400 years old.

Across from the park stands the grand building red of the Carnegie Library with white trim, rebuilt after one of the huge fires that have swept through the city over the course of history. There is still plenty of evidence of the fires in burnt out buildings never razed to the ground and reconstructed and in the fact that so little of the historical architecture remains.

Walcott even wrote a poem called “A City’s Death By Fire”:

After that hot gospeller has levelled all but the churched sky,

I wrote the tale by tallow of a city’s death by fire;

Under a candle’s eye, that smoked in tears, I

Wanted to tell, in more than wax, of faiths that were snapped like wire.

All day I walked abroad among the rubbled tales,

Shocked at each wall that stood on the street like a liar;

Loud was the bird-rocked sky, and all the clouds were bales

Torn open by looting, and white, in spite of the fire.

By the smoking sea, where Christ walked, I asked, why

Should a man wax tears, when his wooden world fails?

In town, leaves were paper, but the hills were a flock of faiths;

To a boy who walked all day, each leaf was a green breath

Rebuilding a love I thought was dead as nails,

Blessing the death and the baptism by fire.

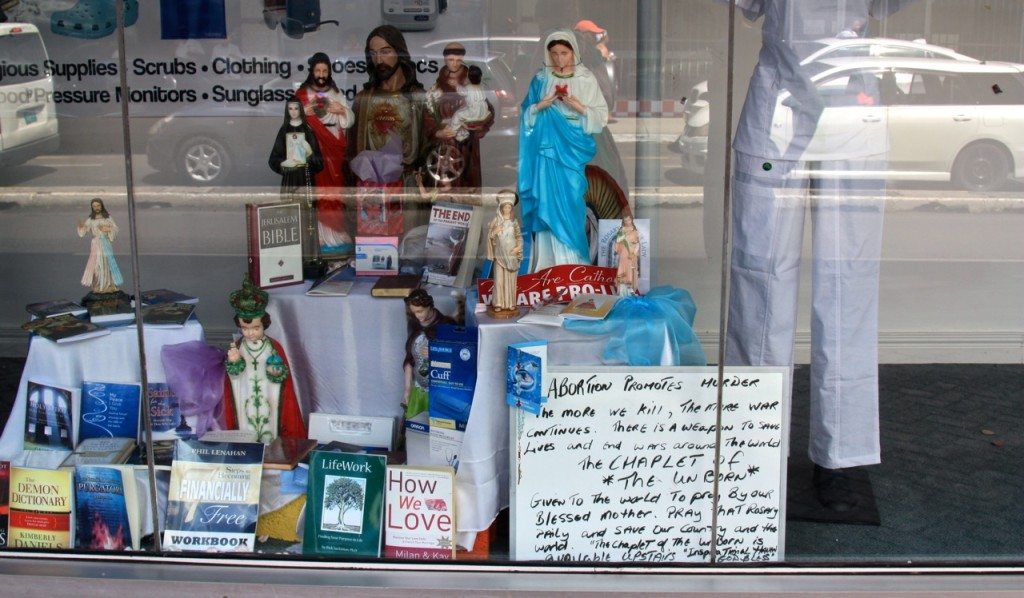

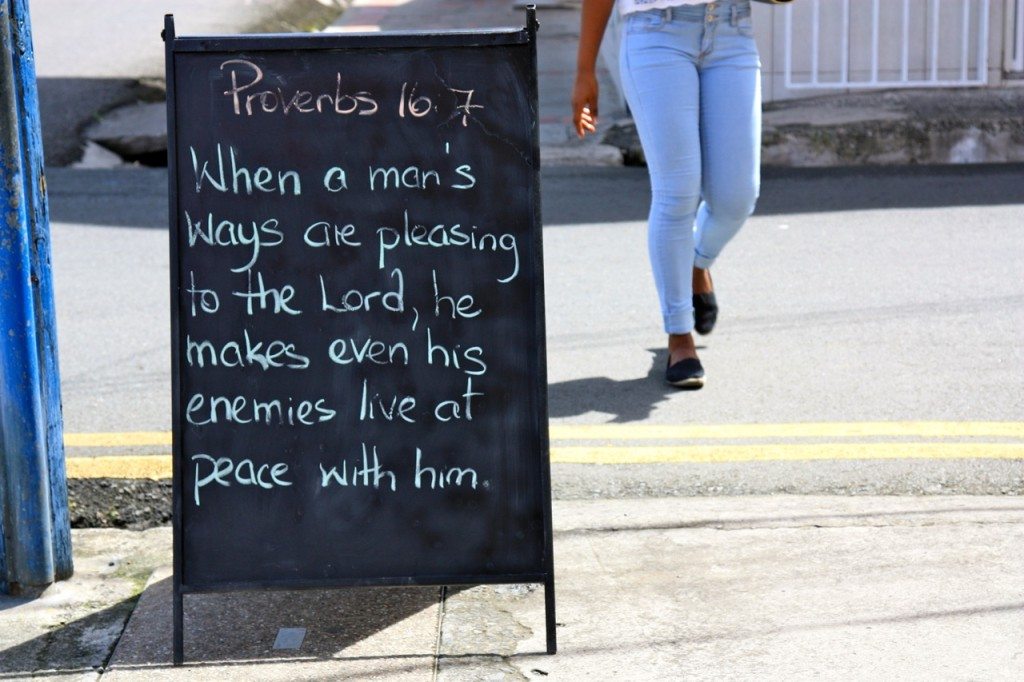

Among the story of the fire, his poem is dotted with snippets of religious reference, something that seems to play a large role in life on the island. Walcott was raised a Methodist in a primarily Catholic society which caused some conflict in his childhood, but religion was and still is important to him. Even outside some of the shops on the streets of Castries, there are chalkboards with religious verses. In windows, displays of Catholic saints and passive poster protests against abortion.

Across from Derek Walcott Square on the opposite side to the library is a Roman Catholic cathedral – the Minor Basilica of the Immaculate Conception. It’s not too much to look at from the outside, but I’m glad curiosity got the best of us and we decided to venture indoors.

It is absolutely stunning artistically. The walls were painted by one of the country’s most famous artists who also designed the Saint Lucian flag. This is Sir Dunstan S. Omer (who happened to be a childhood friend of Walcott). He painted the walls with incredible colourful frescos of black saints with a black Madonna one of the highlights. The Telegraph here in the UK once called him “the Michelangelo of the Caribbean”.

Inside the cathedral, it was deathly silent as cathedrals tend to be. A table of tealights shimmered in the corner. An older woman sat unmoving in a pew, one hand on a cane, just staring toward the alter at the front. We were the only tourists.

It seemed that we were the only tourists much of the time in Saint Lucia, which is really a shame in some ways. While we spent half of our time in a rented house down on the southern tip of the island, we did stay in a resort up north not far from Castries the last five days. While we were there, barely anyone we met ventured much beyond the all-inclusive comforts of the Calabash Cove. And I’m sure many tourists don’t.

On our second visit to Castries, a Disney World cruise ship was docked in the port. I checked, and the ship can hold 2,700 passengers and 950 crew. Being a small city of less than 70,000, we expected to see at stream of other tourists pouring through the streets. But we didn’t. We saw a small trickle, and those we did see were near the central market. All of the others, if they did leave the boat in the full day they were docked, must have stayed near the duty-free shopping area set up specifically for their benefit.

But as we discovered, there’s a whole different story beyond the sun-lounger strewn, white beaches that line the bright blue sea, the unlimited icy and refreshing rum punch to cool you down under the Caribbean sun and those little pockets of built up shopping areas.

There are giant ferns and beautiful rainforests that shimmy under the great booming afternoon thunderstorms. There are acres of banana plantations, hummingbirds darting from tropical flower to tropical flower and old colonial states like Balenbouche with its magical rusted sugar mill, abandoned and unused.

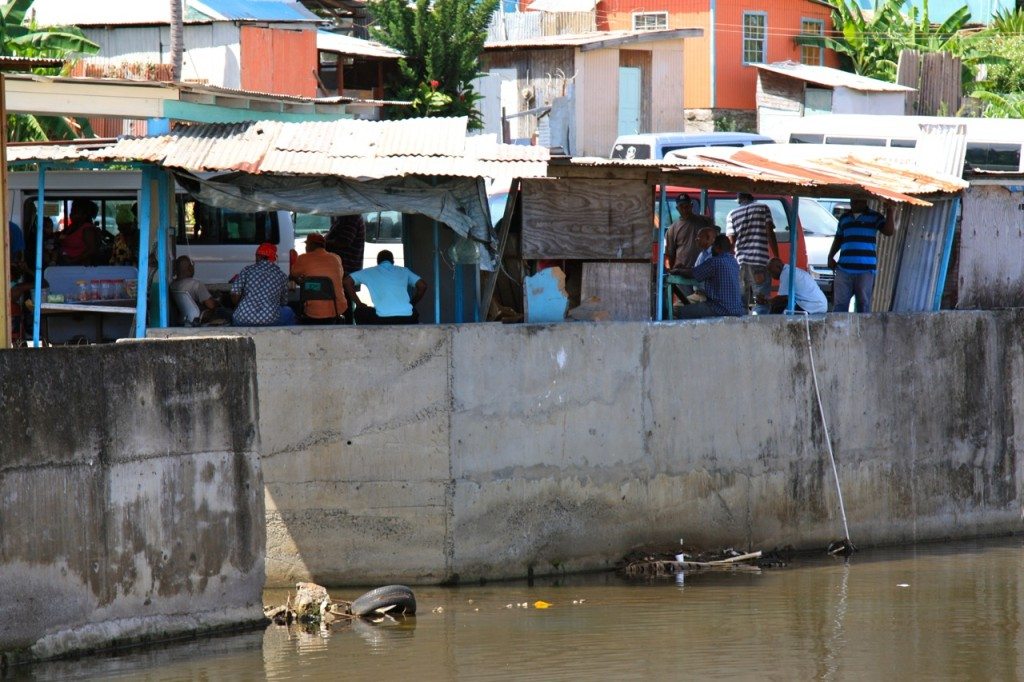

And among that picture of paradise, there is also poverty. A lot of it. Striking scenes of dilapidated homes, kids in ragged clothes, people and women walking up hot concrete hills carrying bags of concrete or food on their shoulders, swinging machetes in an economy that originally built itself on agriculture. It now counts for only 5% of the country’s GDP while tourism has taken over at 80%. Much of the rest lies with the fishing industry.

Ramshackle villages dotted the coast on our drive from Vieux Fort to Castries. When we followed the bumpy dirt paths and stopped to take a walk, we were stared at quite intensely because we were the only white faces in sight. Which was fine and expected, but it meant to us that the little shops and restaurants set up in these struggling villages are catering only to locals. It meant that most tourists aren’t venturing to the villages to spend their money; it is going back into the resorts.

Even in Castries, the biggest city on the island by a long shot, walking the streets beyond the immediate area of the port we were again the only white faces. At one point, on the opposite side of the city, a woman rushed past with a clipboard and said, “Are you with the cruise ship?” When we told her we weren’t, she dropped her voice and said, “Well don’t go that way,” pointing ahead. “Just turn here.”

We listened to her, but of course on our second visit curiosity got the best of us and we ventured a bit closer to where she said not to go because it was the only area of the inner city we hadn’t yet explored. At one corner, we were stopped by a large man sitting on a rickety chair outside a corner shop. “Hey, where are you going?” We replied that we were just wandering around and he said, “Well, I suggest you wander back to the commercial.”

Point taken. In a taxi back to the airport a few days later, our driver was from Castries and we asked if there was an area of Castries where we should go. He said yes, noted the same area – around Leslie Land – where there are drug cartels, violence, a homicide of one of the island’s most notorious criminals, Yulanda Frederick, in one of three separate shooting incidents a few months back. Perhaps cruise ship tourists are told to stay near the port for this reason, though overall, the city did not feel like a dangerous place. I suppose it is confined to the outskirts.

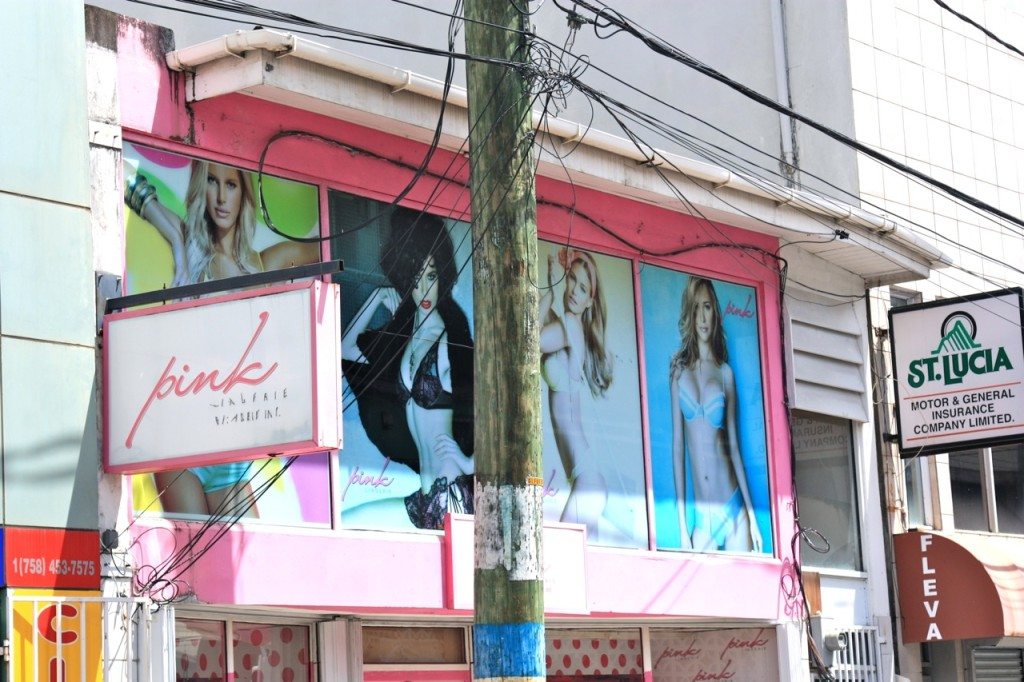

There is a bit of an edge to the city in that it’s a bit gritty, chaotic, some characters walking the streets mumbling to themselves, like you find in any city. The best part of it was probably the buildings, the mishmash of concrete and wood, the hand-painted shop names, the awkward massive advertisement on a lingerie shop featuring all white models in a mostly black country.

I loved the flat cardboard mannequins with accentuated hips, the street vendors with carts of mamones, the row of market stalls where you could buy everything from spices like nutmeg to pure chocolate bars to live crabs to a “little something special” for the potheads on the side if you listen to the whispers in your ear.

There’s music. Reggae mostly, blaring from radios on tables outside of bars. Some of the takeaway joints had security bars like banks do across the counters that you place your order through. There were a multitude of hairdressers and corner shops that sell just about anything to the locals.

The streets are bustling. People are outdoors, living. They’re sitting on porch stoops watching the world go by, chilling on bar stools with their buddies, pushing carts of mangoes up the hill, relaxing on benches, chatting in front of the cathedral, heading home with bags of food to start the dinner preparations. Kids scream in the courtyards of their schools, chasing each other as kids do.

Outside the central market, a woman spots me and says, “Hello sweetie, can I braid your hair? Do you need a bottle of water? We have some nice jewellery in here.” We walk on. I think of a decade-old article I read in the Washington Post before I left, in an effort to learn more about this mysterious country. It was about Derek Walcott, a piece written by Gary Lee, who said that the author wrote about “the odd combination of brutality and sensuality in the landscapes and people, and other peculiarities of Caribbean life.”

It is, indeed, a strange and brutal and sensual place. What Walcott wrote has a large amount of truth in that “if [visitors] surrender to their seeing, [Saint Lucia] has a lot to teach them.”

For more on Saint Lucia, check out Marina’s breadfruit pie recipe, our cocoa plantation tour and lunch at Hotel Chocolat.

1 Comment

Diana Mieczan

November 6, 2014 at 3:27 pmHow interesting. All places around the world have a few different sides and you nailed them all here. I can’t get enough of all those colourful building but you can totally see and feel the poverty and the struggle in those photos. Hope you are having a lovely Thursday, darling.