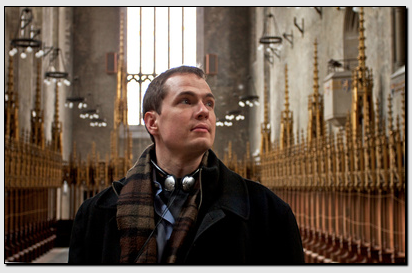

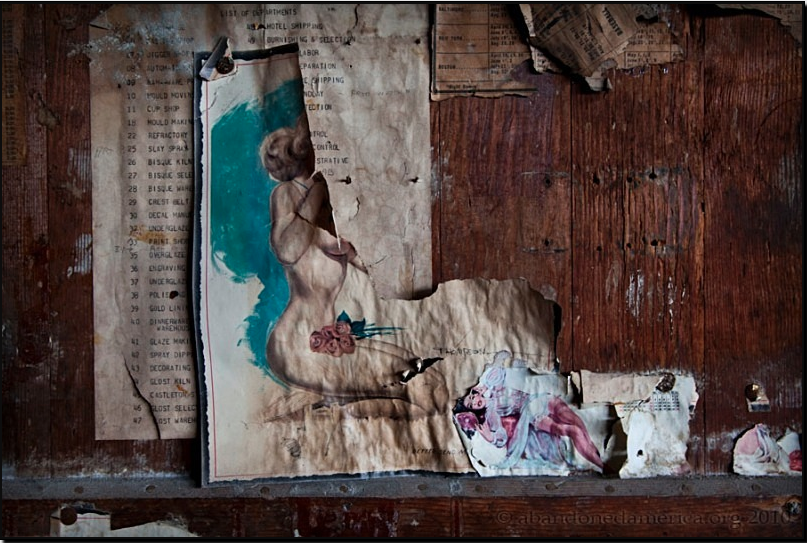

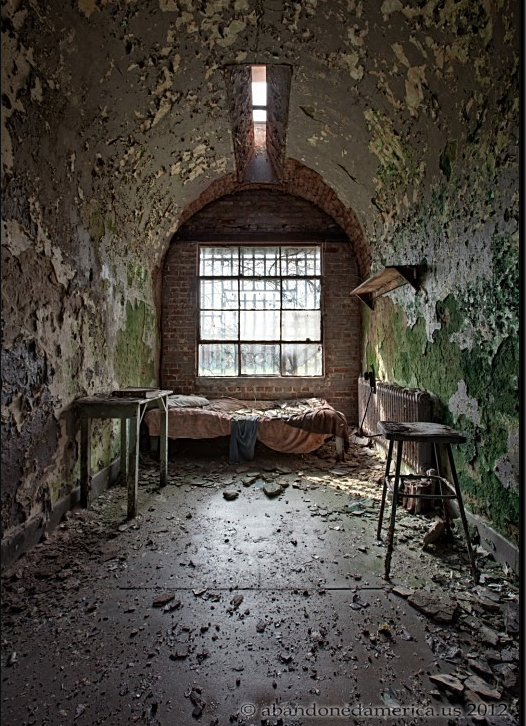

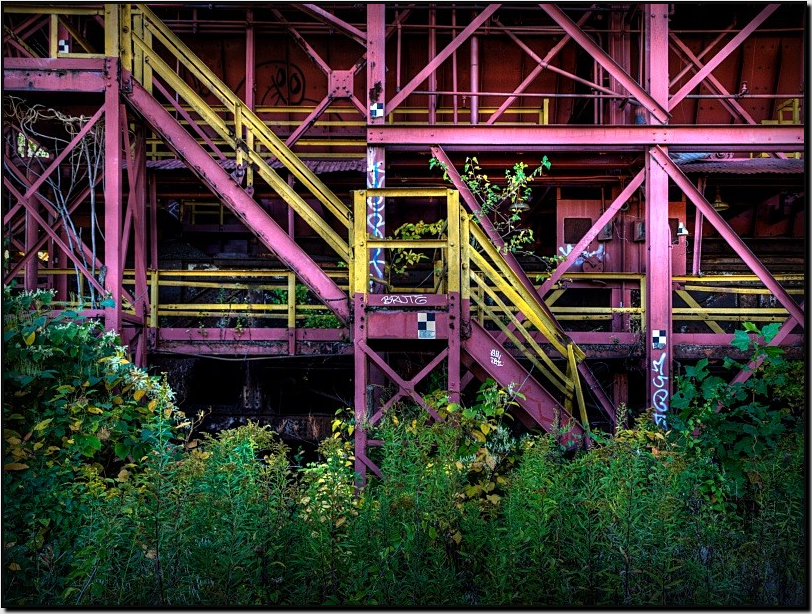

There is a mixture of beauty and sadness in Matthew Christopher’s photography of abandoned places in America. From churches, to schools to factories to mental institutions, Matthew is capturing the buildings that no longer have a place in our world. Many of them have now been demolished. Others have been taken over by nature, plants inching their way through windows, moss growing in crevices. They are full of toppled furniture, posters peeling off the walls, chips of paint like coloured snow covering the floors. Ceilings are collapsing, floorboards caving in, light streaming through windows. Matthew seeks out these places and compiles his images on his website Abandoned America. Below, he talks about why this work is important, the greater meaning behind these images and some of the fascinating scenes he discovers inside.

LO: In a few sentences, tell us a bit about yourself, where you come from, your background in photography and a few things you enjoy outside of your art.

MC: I’m Matthew Christopher, photographer and founder of Abandoned America. I was raised in central Pennsylvania and taught myself photography to communicate what makes abandoned spaces interesting and significant, though I’ve since received an MFA in Imaging Arts and Sciences from the Rochester Institute of Technology. Outside of my artwork, I enjoy learning new things, reading, history, art, nature and music.

LO: You are well known for documenting America’s abandoned spaces through photography and your website. Where does your interest stem from and what drives you to carry on with this ongoing project?

MC: My interest initially grew from research I was doing into the history of mental health care and the asylum system, although it has since grown to encompass all manner of abandoned spaces. I think the subject of blight and economic collapse are very timely and that it is vital that we address what communities become when the sites that formed their identity vanish. Shuttering schools, closing factories, demolishing churches – these all have a profound effect on our way of life. While we tend to think of all movement as progress, I don’t believe the loss of these spaces is advantageous to us. I think it serves as a stark warning about our future as a first world nation and that drives much of my work, although I do also enjoy the act of navigating and photographing these spaces on a more personal level.

LO: Do you remember the very first abandoned place you entered on your own? Where was it? When was it? And what do you remember most about the experience?

MC: That’s a good question. The first I can really recall was a campground in Mount Gretna, the community I lived in when I went to high school. There was an old woman’s house that was badly decayed, a large storage building full of antiques, a carousel that had collapsed and was full of junk, and a few other small buildings. Probably not as interesting as many of the other places I’ve been to. The buildings all burned under suspicious circumstances years later. I mainly remember that they were a good place for my friends and I to get away from our homes. I had very little interest in them for what they actually were at that point aside from enjoying being there.

LO: How do you approach an abandoned space for the first time? What do you look for when you aim your camera? Do you find a place to sit and take it all in or do you wander and take pictures? How long would you typically spend there before you feel you are ready to leave?

MC: That’s tough because each place is different. Usually I am drawn to items left behind, decay, and unique architecture. How I consider framing a shot depends on what combination of the three is in the photograph. I am a fairly slow photographer when I find a place interesting but I will confess that without those elements I can move through a place pretty quickly. I am pretty businesslike about photographing a site. I’d love to have the time to soak everything in first but most of the time I have a small window of opportunity and have to work under the assumption that I will not get to visit again. As such I am pretty methodical and try to be thorough but efficient. When I am working I tend to need to focus solely on that. If I am rushed through a place I can really see the effects on the images I produce.

LO: Do you ever go back to visit or research to keep track of what happens to the places you’ve already photographed? Is that important to you? Why or why not?

MC: I return to places as often as possible and there are a number that I’ve visited once or twice a year for several years now, charting their decline. For the most part I do feel it helps me notice new things and I also get an opportunity to really experience a place vs. being there to work as I described above. I do try to keep on track of developments at sites I visit, and as much as time allows I research them. I wish I had the chance to really go all out in terms of visiting local historical societies, interviewing people who were involved in the sites, etc. At this point photographing sites has kept me very busy and is always the first order of business since one a place is gone, so is that opportunity. I hope to be able to do more thorough research in the future.

LO: Your pictures say a great detail about what you see in these places. Tell us a bit about how they appeal to your other senses.

MC: I’d love to do a more thorough documentation of places. Audio recording would be interesting but often what is striking is the absence of sound, something that is a little foreign in urban environments. It’s hard for me to comment on smells and textures because I all of my energy is centred around producing images. Aside from some of the really overgrown spots which can smell quite pleasant, the only smells that are really striking to me are bad ones – chemicals, dead animals, etc.

LO: Tell us about the most unusual abandoned place you visited. What was memorable about it and why?

MC: Difficult question. Many of them are surreal or unusual, which is another quality I look for. I suppose the ones that are the most decayed are the most unusual; although that isn’t a specific spot, there are a few that I can think of that were very badly deteriorated. What makes them unusual is that you are so much more focused on not falling through the floor or getting injured. You become pretty suspicious of your environment, which is a strange sensation. Seeing areas where the hall you are in has collapsed into the basement three floors below, where you can see through the roof/floors of rooms, where ceiling beams are fanning out as the things on top of them push them down – these are the things that stick with me. It’s hard to select just one spot though, when so many of them are strange.

LO: What do you hope your work will communicate to a wider audience? Why is this project important to you and the larger community that is America?

MC: There are so many things that I think these places communicate that it’s difficult to know where to even begin. I suppose some of the larger overarching themes are about loss and failure, about the way our consumer culture is eating itself apart, about the high price there is to pay for mistakes. I think it asks us to examine our own legacy and era and question why places like these are able to fail and what that means to our society. There are profound lessons that need to be learned when a major factory that was the tentpole of a town goes under, say, due to shipping jobs to other countries with no labor, safety, or environmental regulations, and we also need to ask why we as consumers support the companies that are doing this. Rather than having these critical discussions we are often leaving the factories vacant or tearing them down as quickly as possible and replacing them with service industry jobs and then wondering why our communities are sinking into poverty. I think these places are an omen of what is to come for America if we don’t change course, and while that may sound melodramatic, I have seen far too many places that were far too big to fail and yet did anyway. This is not just work that revels in the visual splendour of ruin, although that is an element. It is work that I hope is frightening and makes people think about what these omens mean. In some ways it is also about what the world will do to repair itself after we are gone.

LO: Is there anywhere you have in mind that you’d love to explore but haven’t yet? Where and what is it and why does it fascinate you?

MC: There are hundreds. I’d love to go to Pripyat/Chernobyl. There are so many overseas locations I can’t even count them all, but Chernobyl is kind of one of the best known and most disturbing abandoned locations in the world. It certainly is one of the more glaring examples of the high price of mistakes when it comes to energy production. I’d love to go to archaeological sites like Angkor Wat in Cambodia where the ruins are much older. I would travel all the time if I could.

LO: What has been your biggest surprise throughout the time you’ve been photographing abandoned spaces? Your biggest challenge? And your biggest reward?

MC: The biggest surprise, challenge, and reward are essentially the same: the fact that people really respond to the subject matter, and the variety of emotions it elicits in them. Some people get very angry at the depictions of these sites for too many reasons even to list. Some people are touched by them and share bits of their own past or experiences, or are moved to consider things in a different light. I’m very lucky for that. It still is a shock to me in a way though, because my own chronicle of my experiences in these places started out as – and still is – something intensely personal and in some ways private despite the fact that it is ‘shared’. I never really expected that it would gain a following or that the genre of work as a whole would rise to such levels of success/notoriety. Managing the responses to the work has been phenomenal and very uplifting on some days when people are kind and insightful and discouraging in others where people try to pick fights with you over the message, presentation, content, and so forth. I have never quite adapted to that. When you put yourself and your work out there you wind up exposing yourself to both a lot of positivity and negativity. Trying to stay focused on the former and tune out the latter is a never ending challenge for me.

Thanks Matthew!

2 Comments

Juliana

April 1, 2014 at 3:15 pmPhotos are beautiful and really full of meaning, but I really really liked the way the artist talks about his experience, work and point of view.

excellent interview!

thanks *

rick moclock

July 16, 2014 at 11:26 pmStunning images of dilapidation/abandonment! I myself enjoyed walking about abandoned farms….textile mills, etc. throughout the Lehigh Valley, Pa. during the 1960’s – 70’s. It would be great to see you document the Neuweiler Brewery and Structural Steel which still stand in dilapidation in Allentown, Pa……..also, Capricorn Records in Macon Ga. I was there in Sept ’13 and the office and studio are in incredible distress for a record label that helped launch an American sound during the 70’s…..Southern Rock.